x #03

Nov.05

|

<1>

Now and again I overhear the same tantalizing rumor.

Hassan i Sabbah (or Hasan bin Sabbah, the Old Man of the Mountains – among other variations) assembled, almost singled-handedly, an army of Ismaili assassins in 11th century Iran. But, the rumor goes, at one point he enslaved a team of Tehran’s greatest stone masons, sculptors, and architects, and he sent them, under guard, deep into the desert. They stayed for ten years.

The Old Man, the rumor goes, had devised a kind of Global Positioning System, at least a thousand years before his time – using sound.

High atop barren, windswept mountain peaks, in the kiln-like heat of central Asia, the enslaved artisans went to work, carving and stacking and aligning walls, polishing rock surfaces, building resonation chambers, applying tiles, tracking wind storms – and listening.

And, in ten years, they were done.

From Baghdad to Alamut, then, Isfahan to Samarkand – and as far away as Morocco, perhaps southern Spain, and some say they even made it to the soggy lands of southeast England – a whole series of towers and earthworks had been constructed.

Disguised as buildings – ruins, even – these constructions were actually marvels of acoustic engineering, part tower, part flute, part earthwork installation. The subtlest breeze could set them off, reverbing through small and twisted chambers, sounds bent and echoed across themselves in low moans and whistles, heavy, endless drones, combinations of notes across all octaves, forming chords.

They were instruments – automatic – played freely by the wind, filling the valleys with spectral sonatinas.

Chamber music.

And this new music of the desert hills, for the army of Hassan i Sabbah – for anyone, indeed, who knew how to listen to the desert – was a sign of where you were: it supplied orientation, cartography, a kind of walkable sonic map, an assassin’s psychoaudiography of the desert.

The music of these valve-houses moved peak to peak, one after the other, across featureless miles, through complex wind instruments built directly into the rocks of unexplored mountains. If you could hear one of the towers – then you knew you were okay; you could never get lost; you could make your way back home across the desert and find the assassin’s secret castle. (This would eventually be their downfall).

Yet today, not all of these towers have been discovered. Many travelers through Central Asia still report hearing strange notes blowing on the nighttime wind, and there is more and more speculation that this comes not from radios in distant camps of fellow travelers, but from the still-functioning pipes and chambers of undiscovered mountaintop wind-instruments, singing quietly to themselves in the darkness.

<2>

To support himself during the War, my grandfather, who owned a cabin on the riverine border between New York State and Canada, eventually found work as a translator. German-raised, having come to the States in the 1920s, he found he could put his own native language to work, translating for the US government.

This soon led to a career in academia, where he began to teach German and German Literature at a small liberal arts college in the woods north of Albany. There, in his spare time, like some kind of monk, he began to translate the journals of his own great-grandfather – who, it turns out, was childhood friends with Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), the great naturalist who mapped the world.

Aside from first names – they were both called Alexander – the two of them shared a love for the outdoors. Humboldt, in fact, made a number of trips down to our old family home in Bavaria where the two of them took long walks into the wooded hills and beyond, ascending the smaller fore-mountains of the German Alps.

At this point my great-great-grandfather Alexander’s journals become subject to doubt; that, or my own grandfather’s translations were suspect. But there was an old manor in the hills, Alexander’s journals explain, that had been built on a site known for its crosswinds that came down and over the mountains from Austria.

The manor’s appearance and architectural style was very strange, however; it deviated quite frequently and unpredictably from the natural topography of the surrounding hills. There were empty chambers with no apparent purpose sprouting from the sides of other empty chambers; there were cylindrical towers too small to house even the smallest child; and there were long, marble corridors that curled round and up the hills – but ultimately led nowhere at all.

This had the effect that you could hear the house before you saw it, a faint whistle just audible beneath the rustling canopies of trees or sporadic bursts of birdsong. Even at night, down in the village, as the families slept – or tried to – the house could be heard, moaning like a tuba; and, it was said, my great-great-grandfather wrote, that you could even tell when the family inside the manor was up and walking around: the notes would change, the tenor of the music, blocked and altered by the movements of the people inside. They were like valves in a saxophone, closing and opening paths of wind.

This was true even down to the position of their furniture. A new banquet table, Alexander wrote, actually changed the sound of the winds so strongly – amplifying them to a kind of endless bass drone – that the townspeople were moved to complain. The table was moved; the sound died away.

When particularly violent winter storms came through, the manor’s residents would take every painting off the walls, tie up furniture beneath tarps, and lock open specific doors and windows that would affect or ease the air-flow – and so it wasn’t thunder at all that the villagers heard, but the old manor house, shaking and booming, roaring with the storm.

The house, of course, was destroyed in World War II, at almost the exact time that my grandfather found himself working as a translator, there in New York State, sitting in his riverside cabin, listening to the foghorns of barges, beneath migrating flocks of geese.

<3>

In defense of the kingdom during World War I, a large array of sound mirrors was constructed along the coast of England.

The sound mirrors were large, upright concrete bowls, specially shaped to reflect – and amplify – the distant droning of enemy airplane engines. They formed a kind of primitive anti-aircraft radar; and so of course were doomed to obsolescence the instant true radar was born.

Monolithic, concrete, abstract, they have sat derelict ever since in the rainswept, grey coastal void, sprayed with graffiti, often half-destroyed by vandals or prolonged neglect.

On the other hand, they have not been forgotten. A few of them are even now listed, Grade II historic structures, an official part of England’s national self-narrative; and a number of ambitious sound artists have proposed ways to recuperate the mirrors’ original function.

Lise Autogena, for instance, “proposes to construct two new acoustic mirrors. One mirror will be placed in Folkestone, filling a gap in the existing chain of mirrors along the English coast. The other will be sited on the coast of France, approximately 25 miles across the Channel. (…) With the aid of the latest in acoustics and communications technology, visitors to the new mirrors… will be able to talk across the sea to those standing on a listening platform in front of the other mirror, on the other side of the Channel” – thus acoustically linking England to France.

A kind of auditory Chunnel.

And yet this project seems rather too humanocentric; the natural acoustic topography of the landscape is already interesting enough without having to whisper to someone in France.

What if, for instance, there were a windstorm that blew through every year on the south coast of England, every autumn, say the first two weeks of November: could you build a new series of sound mirrors, exactly mapped and carefully installed, so as to amplify or prolong the sounds of those seasonal storms? Or to prolong even the storms themselves, which get trapped amidst all those sound mirrors?

In short, could you musicalize the weather through landscape architecture?

People would come from hundreds of miles away just to listen to the hills. The Great November Moan. They’d use a week’s holiday just to listen to the landscape – using sound mirrors.

Imagine, then, a distant gully, moaning at 2am every second week in October, in response to northern winds coming down from the Canadian Arctic. Using sound mirrors, this low droning, cliff-created reverb is then carefully echoed back up the chain of monoliths to supply a natural, continuous soundscape for the sleeping residents of nearby towns.

Or imagine a crevasse that makes no sound at all, but you build a sound mirror nearby: it then amplifies and redirects the ambient air movements, coaxing out a tone – but only for the first week of March. Annually.

It’s a question of interacting with the earth’s atmosphere through human geotechnical constructions.

You’d need: 1) Detailed meteorological charts of a region’s annual wind-flow patterns. 2) Sound mirrors. 3) A very large arts grant.

You could then musicalize the climate.

With precisely placed and arranged sound mirrors atop a mesa, for instance, deep inside a system of canyons – whether that's in the Peak District or Utah – or even Rajasthan – or western Afghanistan – you could interact with the earth's atmosphere to create topographic soundtracks, natural music, for two weeks out of every year, amplifying the natural sounds of seasonal air flows.

People would come, camp out, check into hotels, open all their windows – and just listen to the landscaped echoes.

<4>

There is a Celtic/Arthurian myth of the Hollow Hills: barrow-cities – below ground – where the gods all lived. These formed a linked subterranean labyrinth of domed chambers, with vaulted halls whorling off beneath the Britannic landscape. They’re like something straight out of Tolkien – or Tolkien was something straight out of them: mossy rocks; oily torchlight; graffiti’d runes.

But reimagine these Hollow Hills as engineered by Arup, or even Halliburton, and rebuilt in the 21st century to a design by Zaha Hadid – literal landscape architecture, where the roof is the terrain you walk on. Hollow hills, stretching off to Scotland, looping through Wales, perhaps dipping down for the sub-sea crossing to Northern Ireland, Ireland, France…

Reimagine the Hollow Hills, that is, as a national project, an engineering-based impulse toward mythology.

These new Hollow Hills could be combined with another project I know of – and then we’d be onto something truly unique.

In light of the increasing violence of seasonal storms in the south Atlantic, members of the online architectural journal, BLDGBLOG, were commissioned, in a secret ceremony beneath the Department of Energy’s lowest subcellar, to design, build, and maintain a series of anti-hurricane structures modeled after Virgil’s Aeneid.

It was a strange commission, but far too lucrative to pass up.

As you can read in the Aeneid, “Aeolia” is “the weather-breeding isle”:

Here in a vast cavern King Aeolus

Rules the contending winds and moaning gales

As warden of their prison. Round the walls

They chafe and bluster underground. The din

Makes a great mountain murmur overhead.

High on a citadel enthroned,

Scepter in hand, he molifies their fury,

Else they might flay the sea and sweep away

Land masses and deep sky through empty air.

In fear of this, Jupiter hid them away

In caverns of black night. He set above them

Granite of high mountains – and a king

Empowered at command to rein them in

Or let them go. (Book 1, Lines 75-89)

Directly out of this passage comes the idea for an Aeolian Reef, a series of aboveground, sculpted chambers – think of stainless-steel conch shells, larger than a building, on stilts – that would extend the length and breadth of the American coastline, built in climatologically influential patterns. They would therefore act in concert as a wind-trap, or wind-gutter, grabbing hold of hurricanes and tropical storms and slowing them down – even stopping them entirely.

A hurricane would hit, and – wham! No more hurricane; its winds have disappeared, sucked harmlessly into and dissipated by the Aeolian Reef.

You could therefore use architecture, landscape architecture, to directly influence the climate. This would, in short, be landscape climatology.

Aesthetically, the Aeolian Reef would fall somewhere between Constant's Babylonic mid-sea pavilions –

– and a kind of massive, off-shore, geotechnical saxophone.

Relating it to the present concern – the old Hollow Hills of the Celts – the Reef could be adapted quite easily to the terrain and climate of northern England.

You could replace Hadrian’s Wall, for instance, with a massive, inland Aeolian Reef, embedding it into the hills of Yorkshire. It would span the breadth of England, and its sculpted, sunken chambers, full of valves, could alter weather all over the country. You could actually guarantee sunshine in the summer, saving garden parties from inevitable drizzly showers; more important, you could make the climate constant, trustworthy, regularized.

Taxable.

This would come with an as yet undetermined effect on the British national character.

That, or you could make music with it: the world’s largest terrestrial pipe organ. The Hill Flute. An enormous, trans-Britannic wind instrument embedded in the moors of Yorkshire.

It would be cavernous – huge – and the air in this complex of neo-Arthurian, steel-lined, vaulted tubes would be in a state of near-constant musical excitement.

<5>

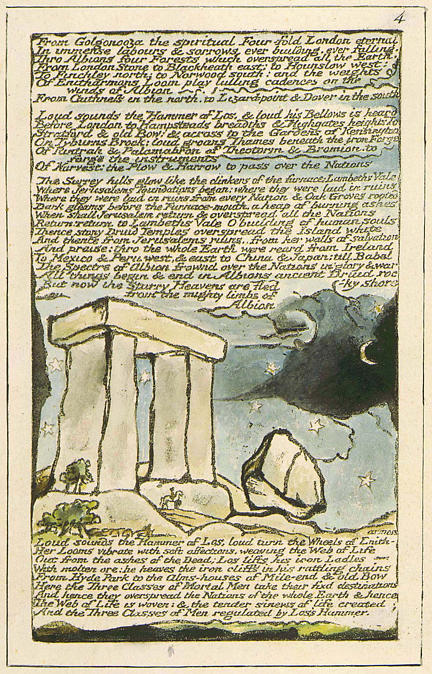

As William Blake describes the city of London in his epic poem “Milton” –

...spiritual Four-Fold London eternal

In immense labours & sorrows, ever building, ever falling (...)

From London Stone to Blackheath east: to Hounslow west:

To Finchley north: to Norwood south: ...the weights

Of Enitharmons Loom play lulling cadences on the winds of Albion

– we find the city portrayed as a kind of vast musical instrument, emitting lulling cadences through (perhaps even as) “Enitharmons Loom.”

This is the city-as-instrument.

All cities are instruments, however, whether through the rumble of Berlin’s U-Bahns, the tectonic drone of L.A.’s subterranean plates, or the endless constructive roar of Shanghai.

“Venice has got a very different sound,” musician Christian Fennesz tells The Wire. “It’s very interesting, when you’re there, you always hear some kind of hum, like from far away, but also people talking, and you never know if it’s in the next apartment or if it’s 400 metres away, because the labyrinth of the houses works as an amplifying system somehow.”

Putting this in the context of William Blake’s London, that vast Loom, played by a thousand, micro-meteorological winds, re-echoed building to building down the labyrinths of wet streets, I would like to propose the following:

We will turn the derelict stations of the London Underground into subterranean resonation chambers. We will fill them with Aeolian harps, for instance, which need nothing other than a steady breeze, and we add rattles and hollow pipes – tubes within the Tube – and these would all catch the passing drafts of everyday trains.

The Tube as buried oboe. Lined with rare and sonorous woods, like a Stradivarius.

London Instrument.

The abandoned Tube stations hundreds of feet below London would then emit low drones, recycling stale air into reverb, greeting you sonically as you passed by, filling your Tube carriage with a snatched fragment of music.

All cities have a sound; this would be London’s. Mournful; subterranean; constant.

<6>

As we began in the desert, we will end in the desert.

“Sand dunes in certain parts of the world are notorious for the noises they make, as sand avalanches down their sides,” the New Scientist reports. “Some emit low powerful booms, others sound like drum rolls or galloping horses, and some are even tuneful. These dune songs have been reported to last for up to 15 minutes and can sound as loud as a low-flying aeroplane.”

To test for the causes, properties, and other effects of these sand dune booms, “Stéphane Douady of the French national research agency CNRS and his colleagues shipped sand from Moroccan singing dunes back to his lab to investigate.”

There, Douady's team “found that they could play notes by pushing the sand by hand, or with a metal handle.”

Thus we witness the transformation of a sand dune – and, by extension, the entire Sahara desert, indeed any desert – even, by extension, the rust deserts of Mars – into a musical instrument.

Music of the spheres, indeed.

As Elizabethan English court magician John Dee once wrote: “The entire universe is like a lyre tuned by some excellent artificer, whose strings are separate species of the universal whole. Anyone who knew how to touch these desxterously and make them vibrate would draw forth marvelous harmonies.”

In any case, “When the sand avalanches, the grains jostle each other at different frequencies, setting up standing waves in the cascading layer, says Douady. These waves reinforce one another, making the layer vibrate like the surface of a loud speaker. ‘What’s funny is that in these massive dunes, only a thin layer of 2 or 3 centimetres is needed to set up the resonance,’ says Douady. ‘Soon all grains begin to vibrate in step.’”

Douady has so perfected his technique of dune resonance that he has now “successfully predicted the notes emitted by dunes in Morocco, Chile and the US simply by measuring the size of the grains they contain.” The music of the dunes, in other words, was determined entirely by the size, shape, and roughness of the sand grains involved, where excessive smoothness dampened the dunes’ sound.

The very existence of these sounds, however, should not be surprising – because the earth itself is already a musical instrument: there is “a deep, low-frequency rumble that is present in the ground even when there are no earthquakes happening. Dubbed the ‘Earth’s hum’, the signal had gone unnoticed in previous studies because it looked like noise in the data.”

Elsewhere: “Competing with the natural emissions from stars and other celestial objects, our Earth sings like a canary – it drones on in a constant hum of a gazillion notes. If it were several octaves higher,” it would even be “audible to the human ear” – like subways passing beneath sidewalks.

All of which, finally, brings us to Ernst Chladni and his Chladni figures, or: architectonic structures appearing in sand due to patterns of acoustic resonance.

Architecture through sound and sand. Silicon assuming structure. Desert harddrive, humming.

The gist of Chladni's experiments involved spreading a thin layer of sand across a vibrating plate, changing the frequency at which the plate vibrated, and then watching the sand as it shivered round, forming regular, highly geometric patterns. Those patterns depended upon, and were formed in response to, whatever vibration frequency it was that Chladni chose.

So you’ve got sound dunes, terrestrial vibration, some Chladni figures – one could be excused for wondering whether the earth, apparently a kind of carbon-ironic bell made of continental plates and oceanic resonators, is really a vast and spherical Chladni plate, vibrating every little mineral, every pebble, every grain of sand, perhaps every organic molecule, into complex, three-dimensional, time-persistent patterns for which we have no standard or even technique of measurement. Or maybe William Blake knew how to do it, or Pythagoras, or perhaps even Nicola Tesla, but…

The sound dunes continue to boom and shiver. The deserts roar. The continents hum.

The planet is, forever, Aeolian.

gmanaugh at movingsurface.net

|