x #01

Mar.05

UTOPIA

|

The socio-politics of the post World War II era was marked by profound changes in the global parameters of social relations of hegemony. The capitalist world system was reconfiguring itself, reconstituting its institutions; while at the same time being confronted by antisystemic political thought and action. This antisystemic challenge matured and developed into an antagonist political dynamic in the 1960s; reaching its peak point in the events of May 68 in Paris, which “profoundly and irrevocably changed the political ground rules of the world-system” (Arrighi et al., 1989: 98). Situationist International, a political group of dubious reputation (1957-1972), emerged out of this political climate and produced a radical critique of the world-system being established in the postwar years. Problematizing the social phenomena that characterized this era, Situationism developed a revolutionary program of action that involved both actual and potential social change.

Situationist International is often regarded as a marginal political group whose only significance might have been helping May 68 happen. Or elsewise, it is viewed as a short-lived avantgarde artistic movement whose fate has been no different from the others of its kind, in terms of losing out the battle against hegemonic powers and eventually being absorbed by the culture industry. So it is no wonder that Situationism has remained confined to its cliché interpretations—if not out of sight—for about three decades. Its opponents dismiss it altogether for being contradictory, indeterminate, agonist, feverish and perverse; for they think these qualities signify flaws in politics. And the proponents make a myth of it thus miss its complex nature. Eventually, all these views contribute only to the obscuration of Situationist politics, instead of making room for its critical potentials to unveil.

However, lately, a growing body of work is trying to take Situationism beyond cliché frameworks. Particularly within the last decade, there is an attempt to rethink Situationism, to discover its political potentials, and to reclaim its political and theoretical value[i]. Joining this endeavor takes some effort. To do justice to the questions raised by Situationism, one should first of all break away from the controversy surrounding it, that which seems to settle for stereotypical interpretations. In fact, there is much more merit in beginning to treat Situationism as a historically situated, legitimate political movement. Once this is done, Situationism becomes intriguing in many respects, among which, one is the most salient for the purposes of this paper: That Situationist politics is deeply rooted in issues of space; and in this sense, it clues one in conceiving the relationship between the politics of space and revolutionary practice.

Situationism produced a radical critique of the postwar consumer society and nourished a strong desire for changing it. To pursue this change, Situationists struggled on two main fronts. The first front involved transforming the actual and seemingly trivial everyday life, by immediately intervening in it thus challenging its given order. This immediate urge for change was to be realized first of all for its own sake; but it also had a broader intention. Situationists expected that immediate intervention would give everyday life a revolutionary turn; and that would ultimately lead to supervention. Hence the second front of Situationist political struggle involved conceiving total change in the long-term. While carrying out the battle at the level of everyday life, Situationists were also engaged in a utopian imagination to delineate the prospects of a future society in its entirety—a society free from the hegemonic social relations determining the existing one.

It is necessary to emphasize here that, for Situationism, these two fronts of struggle are intertwined matters of concern rather than discrete, specialized domains to be dealt with separately. Nevertheless, this does not necessarily mean that the two fronts are in harmony with each other. On the contrary, they are in constant conflict. These two fronts reflect Situationism’s two equally maintained desires that are indeed in an antinomic relationship to each other. This antinomy is decisive to understand Situationist thought. And doubtlessly, it looms large in Situationist politics of space, for it is often regarded as an incompatibility. Apparently, to a good many people, it sounds dissonant to intervene in everyday life immediately and partially while at the same time devoting a serious effort to imagine a future spatiality in its totality. In fact, these two desires become even more antinomic in the project New Babylon, the outcome of Constant’s 18 years-long experimental practice to sketch out ideas for “another city for another life”[ii].

Constant Nieuwenhuys (known as Constant) was a founding member of the Situationist International; and although he remained a member only for three years, his work on the New Babylon continued to have indispensable ties to the spatial politics of Situationism[iii]. As a matter of fact, Constant’s New Babylon and the Situationist politics of space share the twofold political desire for change. The utopian tendency towards unity and totality and the desire for total (macro) change, when situated along with the down-to-earth urge to carry out partial alterations in everyday life by way of (micro) tactics, the question of incompatibility arises for Constant’s work as well. This paper will not take this seeming incompatibility for granted. Instead, it will look deeply into it and try to explore the following question: If we look at Constant’s New Babylon against a backdrop made up of Situationist politics of spatiality, how does this antinomy appear to operate in-between the two contradictory, but equally strong political desires?

Therefore, in this paper, I will try to understand what kind of an effect this antinomy produces, by focusing on the visual and the theoretical legacy of Constant and Situationism. I will argue that the antinomy involved in Situationist conception of spatiality produces a tension, which, in turn, generates a constructive effect that gives Situationist politics of space its vitality. And the New Babylon, once celebrated by Debord as “the most advanced manifestation of the group’s efforts”, is where this tension is most manifest thus the antinomy perfected (Wigley, 1998: 16). Therefore, the New Babylon promises to be the most fruitful subject matter to look at, in order to explore the ways in which political indeterminacy, or antinomy pushed to its extreme ends could well generate a constructive (rather than a destructive) political effect.

To begin with, I will give an overview of the global socio-economic context in the postwar era and its implications regarding everyday life. Then I will go through Situationist concepts of spatiality and expand them for further discussion. After discussing the forms these concept take in the New Babylon, I will conclude with remarks on how the perfected antinomy and the sustained indeterminacy in Situationist thought contributes to the ways in which we conceive the relationship between the politics of space and radical social change in the present.

The Post World War II Era—Politics, Culture, Urbanism

The years following the end of World War II witnessed the establishment of the United States-centered hegemonic world-system, and the consolidation of its institutions through political, economic and cultural means. With the onset of the Cold War thus the division of the world into two camps, United States started its worldwide operations against the Soviet challenge. The launch of the Marshall Plan was one of the first operations, which not only carried with it the financial means to rebuild the war-torn European countries, but also helped protect the European nations against fears of Soviet domination[iv]. More importantly, it spread an anti-communist ideology into the cultural landscapes in question, and paved the way for worldwide Americanization.

Guy Debord’s influential book The Society of the Spectacle derived its clues from such a socio-political context (Debord, 1995). Having completed its domination over production, postwar capitalism was leaping fast forward, by laying the foundations for new kinds of hegemonic strategies concerning the realm of consumption. As termed by Debord, “the spectacle-commodity system” (as “a worldview translated into the material realm”) was giving shape not only to the public/social life, but also to the private sphere (idem, 13). With the culture of mass consumption securing its position, “the colonization of everyday life” was already under way (idem, 29). For Debord, the spectacle operated either in “concentrated” or in “diffuse” form (idem, 41). The concentrated spectacle was the repressive bureaucratic state power that transformed the ways in which political-economic powers operated throughout the world. Besides, the diffuse spectacle represented the hegemonic ideology that was at work within both the public and the private realms[v]. Thus the spectacle penetrated everyday life in all its aspects, within a range from ways of thinking to ways of dwelling[vi].

With this inevitably came the transformation of cities according to the requirements of the spectacle-commodity system. Before all else, in postwar America, urban space was subjected to a reorganization in line with the glorified ideology of “the American dream” and the lifestyle it was said to accommodate. As symptomatic of the consumer society, postwar urbanism in the United States was based mainly on two mass consumer commodities; private automobile and standard housing[vii] (Ross, 1995: 4-5; Cohen, 2003: 195-199). This form of urbanization, known as urban sprawl, required the dispersal of the elements that made up urban space: bedroom suburbs, deserted downtowns, shopping malls along the highways. Suburban life (as the typical residential environment), together with the shopping malls (as the standardized halls of mass consumption), helped to ensure the survival of the socio-economic system. Consequently, public space lost its vitality in social life, gradually bringing along the isolation of the inhabitants of cities in their private spaces, thus the decline in the quality of social life altogether[viii].

In connection to this, this era also saw the rise of domestic technologies that helped shape and control the private realm. As in the case of television, technology entered the domestic interior and began to determine private life[ix]. In opposition to the claims that technology liberated human beings by bringing freedom and comfort into everyday life, Debord argued that it in fact impoverished its quality. Pointing to the relationship between capitalism’s entry into the private realm and the degeneration of everyday life, Debord writes:

This introduction of technology into everyday life—ultimately taking place within the framework of modern bureaucratized capitalism—certainly tends rather to reduce people’s independence and creativity. The new prefabricated cities clearly exemplify the totalitarian tendency of modern capitalism’s organization of life: the isolated inhabitants (generally isolated within the framework of the family cell) see their lives reduced to the pure triviality of the repetitive combined with the obligatory absorption of an equally repetitive spectacle. (Debord, 1961: 71)

This was followed by the migration of the American type of urbanism to many other socio-geographies. France—as a country receiving the Marshall Aid—was subjected to this process. Kristin Ross’s account on how French culture was changing at the time is helpful here[x]. To trace the broader social transformations in French daily life, Ross looks at French intellectual life and asks an incisive question: “Why were so many of the French intellectuals reflecting on everyday life in that period?” Indeed, why was “everyday life elevated to the status of a theoretical concept at this particular conjuncture”? (Ross, 1995: 5). For Ross, the French social landscape saw abrupt changes with “the sudden, full-scale entry of capital” into everyday life. And this entailed a new cultural regime governing not only the public both this time also the private sphere, which henceforth fostered its critique (idem, 6). As part of the process of “Americanization”, new ways of dwelling (the suburbs), transport (the private automobile), new communication technologies (television), along with consumer goods and the boom in their promotion (the advertisement industry) left irretrievable marks on French culture[xi].

Situationist Concepts of Spatiality

Against the backdrop of postwar urbanism, Situationism came up with a kind of spatial politics that proposed to disrupt the hegemonic spatial organization and ultimately aimed to change it altogether. A foundational spatial concept Situationists developed was “constructing situations”, which meant the creation of open-ended, participatory, collective situations that would make it possible first to criticize, then to disrupt, and finally to transform the currently pervasive urbanism. This required a political consciousness that would let one generate openings of liberation in the usual course of everyday life, which was presumed to be flowing in a smooth and orderly fashion[xii].

To realize the disruption in the first place, the Situationist tactic détournement was to be put into use (Debord / Wolman, 1956: 8-13). Détournement was originally a pre-Situationist concept, which was applied to writing and art during the time of the Lettrists. Its meaning can be met by various concepts such as deflection, diversion, rerouting, distortion, misuse, misappropriation, or turning aside from the normal course or purpose. With regard to space, détournement involves a direct intervention into “established places”. By appropriating the proper and liberating it from its presumed order, one makes it destable thus gives birth to an indeterminate state of affairs. For Situationism, facing this indeterminacy was the crux of the matter, because in it lay the potential for actual change. Once the possibility to use the proper improperly was created, one could take a step forward, deliberately misuse this possibility, and eventually change it.

Psychogeography is another Situationist concept that suggests a possibility of change. It conceives of the production of urban space by way of an interplay between space and its inhabitants and proposes a politics of ambience created through this interplay[xiii]. Simultaneously involving unconscious and conscious appropriations of urban space, it reflects yet another indeterminacy in which the inhabitant oscillates between passivity and activity. Psychogeography definitely involves passivity, but it is not just about submitting oneself unconsciously to the given urban atmosphere and contenting with it. It also requires a self-conscious political activity intended at achieving emancipation.

This way of seeing the relationship between the physical environment and the social life it houses suggests a search for harmony, or a longing for a lost unity and totality—leading us to the Situationist concept of unitary urbanism[xiv]. Almost like a catchword coming up in many Situationist writings, unitary urbanism very well reflects the utopian tendency in Situationism, for it seems to involve an idealization. In fact, to a considerable extent, it does involve imagining an integrated whole. Nonetheless, it is more complex than a dogmatic set of ideas. Although unitary urbanism definitely demands a motive to foresee the prospects of an integrated future society, it does this in a less determinate than an indeterminate manner.

Unitary urbanism is meant to be a flexible and adaptable concept. It is less a prescription than a facilitator to make room for “the freedom to change our way of life” (Niewenhuys, 1960: 132). It aspires to an integrity, but not to a fixed unity; on the contrary, it proposes a ceaseless transformation of our current habits and lifestyles. In a nutshell, then, unitary urbanism can be defined as a set of preliminary propositions to experiment with, in order to envision a future spatiality in a revolutionary way. Summing up all the other Situationist concepts of spatiality, it confronts the restrictive structure imposed on social life by the functionalism, universalism and totalitarianism of modernist urbanism.

Dérive is another significant spatial concept elaborated by Situationism. It means drifting, and it has a primarily urban character. It is a continuous wandering around the city, passing through its varying ambiences, opening oneself up to the psychogeographical effects of its spaces. It has to do with chance encounters, however, as Debord notes, chance encounters offer limited possibilities, therefore one has to go one step further to practice dérive. For Debord, dérive is a “playful” (ludic) but at the same time a “constructive” behavior, which calls for an awareness of the limits of chance thus a state of “being on the watch”—so as to be able to seize the moments in which chance reduces experience to habit[xv] (Debord, 1958). In this respect, dérive is a deflected, distorted, diverted—détournée, if you will—use of urban space. In other words, it is a call up for “the misuse value of space”[xvi], which is synonymous to what Thomas McDonough calls “the political use of space”:

Dérive as a pedestrian speech act is a reinstatement of the “use value of space” in a society that privileges the “exchange value of space”—that is, its existence as property. In this manner, the dérive is a political use of space, constructing new social relations through “ludic-constructive behavior”. (McDonough, 1994: 75).

A politics of space could only stem from the most trivial aspects of everyday life—actually full of hidden nodes of attraction and endless flows—as opposed to the urban functions predetermined by urban planning. Dérive, in this sense, is a subversion of the existing structure of the city. This is akin to Michel de Certeau’s account on everyday life practices. For de Certeau, “the rule of the proper” is what governs “the place” and attempts to fixate it; but this attempt is diverted by the users of space, through whose practice “place” transforms into “space” (de Certeau, 1984: 117-118). Similarly, in Situationist conception of spatiality, “space” is practiced “place”—just as in de Certeau’s case of the street designed by urban planners, which would only become a space by the act of walkers (ibidem). Therefore, space is a relation, rather than a thing in itself. de Certeau writes:

Space occurs as the effect produced by the operations that orient it, situate it, temporalize it, and make it a function. (…) In relation to place, space is like the word when it is spoken, that is, when it is caught in the ambiguity of an actualization, transformed into a term dependent upon many different conventions, situated as the act of a present (or of a time), and modified by the transformations caused by successive contexts. In contradistinction to the place, it has thus none of the univocity or stability of a “proper”. (de Certeau, 1984: 117).

This takes us to the last—but not the least—significant spatial concept in Situationism: social space. Social space does not simply correspond to “public place”. It is not merely a physicality, not only a container in which social interactions take place. Instead, it can be defined as a social relation, involving space’s production as well as reproduction. In Situationist thought, social space is synonymous to everyday life, just as in the theoretical framework delineated by Henri Lefebvre to understand the production of space[xvii]. In his analysis of the production of space, Lefebvre develops a spatial trialectics, which consists of three categories. “The physical” involves spatial practices, referring to the use value of space. “The mental” (or “the conceived”) is embodied in representations of space thus its exchange value. And “the social” (or “the lived”) encompasses spaces of representation, corresponding to what I call its “misuse value” (Lefebvre, 1991a). As Debord also remarks, under advanced capitalism, the second category (exchange value of space)—as the ultimate form of abstraction / reification— “rules over all lived experience” [xviii] (Debord, 1995: 26). Situationism takes a position against the exchange value of space; stands up for its use value; and more importantly, it evokes its misuse value. For Situationism, a revolutionary politics of space could emerge only through social space (or “the lived”), which urgently needs to regain primacy over abstract space.

Situationist Space Materialized—The New Babylon

Constant was a Dutch painter, who abandoned painting due to “the dissatisfaction of a modern artist who no longer believed in superior individual creativity”. Striving for “an art that would be public and collective in a way that easel painting could never be”, he started to work on the project New Babylon, in which he tried to draft a revolutionary conception of spatiality (Wigley, 1998: 67). For Constant, working on the New Babylon meant both theoretical reflection and concrete production of forms; and in both, the process itself was much more important than the endproduct. For that matter, the performative potential of presentations and exhibitions were of great significance. Pertinently, the images of the New Babylon were intended less as representations of spaces than as attempts to animate spatial experiences[xix]. In Constant’s words, the New Babylon was “not a town-planning project, but rather a way of thinking, of imagining, of looking on things and on life.” (idem, 62).

The New Babylon comprises a set of texts in which Constant tries to develop ideas for a future city; along with models and images conceived as illustrative elaboration of those ideas. Constant’s work certainly involves a projection into the future, yet at the same time it is meant to be played with today (ibidem). In the concrete production component of his work, Constant makes use of various mediums of representation ranging from architectural drawing, model-making, painting, lithography, photomontage to music and film; going beyond the disciplinary expectations of any specific medium[xx]. By way of this transdisciplinary effort, he seeks to surpass conventional notions of representation. In other words, by forcing the limits of representation, Constant tries to see through abstraction and looks for emancipatory ways of giving form to lived experience.

Alluding to Constant’s interrogation of representation, here I will attempt to understand the possibilities offered by the images of the New Babylon, rather than taking them as frozen, abstract forms. The five images I choose to analyse are not necessarily meant to be epitomic “representatives”; instead, I prefer to see them as visual experiments with representation, having strong suggestions of the spatiality Constant tried to conceptualize. So, I will also take the experimental way; and go through the images in a quite disorienting fashion. Switching between scales and mediums, I will try to grasp the ways in which these images bear the seeds of featuring “lived experience”.

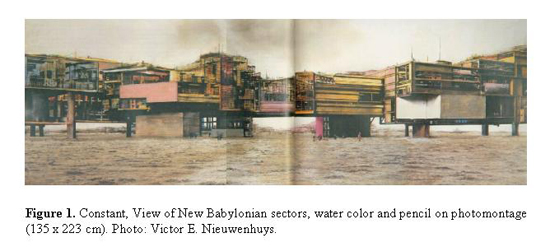

I will start with one of the later images produced by Constant. In this image titled “View of New Babylonian Sectors”[xxi], Constant brings together photographs of some of his models in a photomontage and modifies it by drawing and painting (in pencil and watercolor) [xxii] (Figure 1). The image is the depiction of a gigantic architectural structure spanning a vast terrain. It consists of an empty field, above which stands a series of New Babylonian sectors. On the ground level, which is supposed to be spared for motor vehicle traffic, there is only a few (barely visible) human figures. On the second level, which is the underground, a fully automated industry run by machines is said to be buried. The main living areas are elevated high above the ground level, forming the last major level of the tri-layered city. The elevated spaces are completely covered; they are fully lit, ventilated and air-conditioned by artificial means. In this imaginary city, the inhabitants are liberated from work by means of full automation, in favor of constant leisure. Everyday life is restored to its integrity. The city is shaped in such a way that the inhabitants are free to modify its spaces should they desire. A collective reconstruction of social space is constantly going on, in favor of an intensified lived experience.

This is an extremely phantasmagoric image. At the same time, it attempts to capture almost all the principles of unitary urbanism in a cohesive way, which makes it suggestive of a totalizing point of view. In a sense, it is less akin to a non-deterministic way of conceiving urban space than to a resolution-oriented one. One can easily take this structure as project of monstrous fantasy; one suffering from the unfeasibility of an idealist utopian imagination. Just as Wigley notes: It “might be the liberating way of the future, or it might just as easily be a nightmarish high-tech pleasure prison. Either way, it is a shock.” (Wigley, 1998: 12).

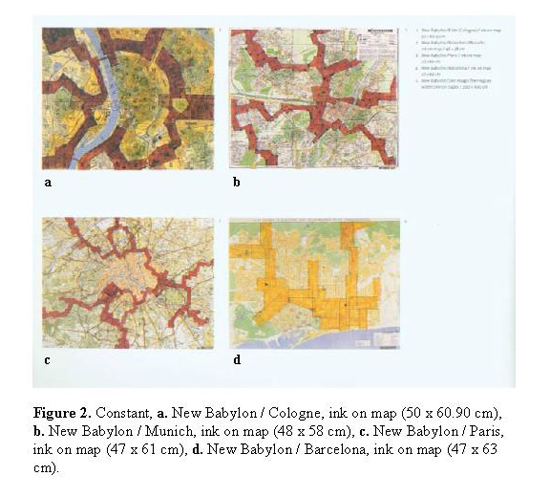

Such a totalizing view of urban space is also apparent in Constant’s appropriated maps, each of which features a New Babylonian city superimposed onto the existing urban layout (Figure 2). In the background, we see the actual maps of Cologne, Munich, Paris, Barcelona, whereas in the foreground there are four different New Babylonian patterns of settlement, each tailored to fit its background. The New Babylonian settlements, which clearly follow the contours of what is lying underneath, are depicted in the form of monochromatic stains, making each image a highly diagrammatic representation[xxiii]. In these appropriated maps, the given urban condition appears to be an input for Constant. Instead of disregarding the given reality (as idealist utopian visions would have it), he develops an awareness of it. In other words, even when pursuing fantasy, Constant has a “realistic” tendency, which pushes his work out of the realm of idealist utopia, and furthermore, complicates the question of what the New Babylon aspires to be.

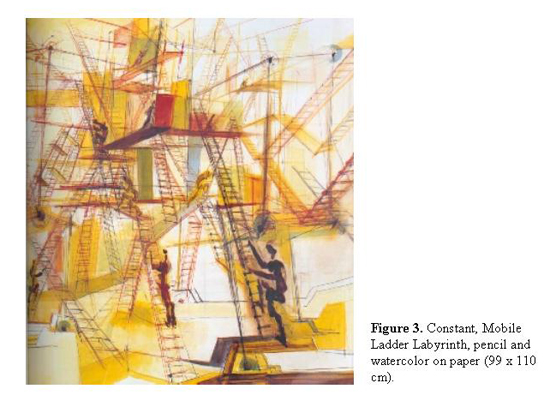

Constant’s imagination seems to become even more divergent as we encounter an image like the “Mobile Ladder Labyrinth” (Figure 3). Due to its minimal scale, this image may be located to the other end of the spectrum constituted by Constant’s varying scales and mediums of representation. “Mobile Ladder Labyrinth” is a drawing in pencil and watercolor, in which there are ladders connected to a labyrinthine structure in unexpected ways, along with human figures attached to them—climbing or standing. We cannot tell whether this labyrinthine space is located indoors or outdoors, nor can we determine whether this image is realistic or not. The mobile ladder labyrinth gives one a dynamic sense of space nevertheless. This dynamism is achieved partly by means of creating an optical illusion of the third dimension thus rendering the two-dimensional medium spatial. Also, the chaotic and dynamic nature of the labyrinthine space is reminiscent of the many ambiences that the New Babylon is supposed to foster. Most importantly, by exceeding the limits of representation determined by its medium, this image activates the viewer in favor of imagining lived experience.

Constant’s endeavor to imagine what an ambience could look like, his inexhaustible energy and restless attempts to visualize this imagination include yet another technique of representation, which is lithography. In a series of ten lithographs that animate scenes from the New Babylon (Figure 4), Constant comes closer to a film-maker rather than an urban designer. The lithographs remind one of story-boards, produced by film-makers to imagine the atmospheres of film scenes in advance of staging and shooting them[xxiv]. The affinity between Constant’s lithographs and cinematographic story-boards is telling, because cinema is a medium of representation that proves to have an extensive potential to push the limits of representation[xxv].

The first lithograph covers a vast empty land represented as a large red stain, towards the upper right side of which a hardly legible New Babylonian structure is placed (Figure 4-a). Another one (Figure 4-h) contains lines, planes and colors that intersect, overlap, extend over each other in a disorderly fashion. There is yet another one that gives one a strong sense of the dérive. The last lithograph (Figure 4-i), all in black and white, is made up of overlapping lines and planes, with points of concentration here and there, and a sign of movement through space. Among the ten lithographs, this is the one most heavily loaded with suggestions of Situationist space. It communicates its viewer the intensiveness of a constructed situation. The hyperbolic movement resembles something between a trajectory and a cycle; it looks as if it is inscribed in space by somebody practicing dérive. One could sense the force fields created by the flow of desires through space; and even the tensions generated by these flows.

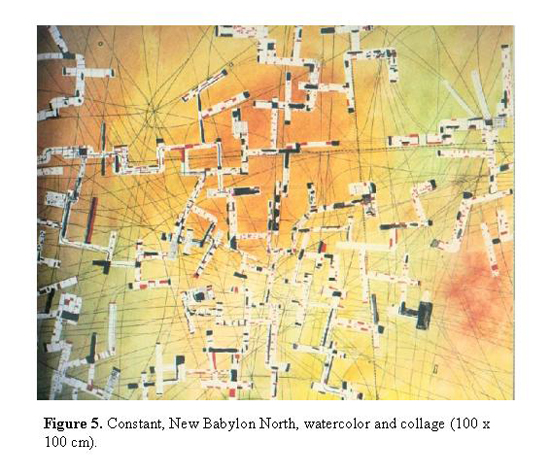

Yet Constant’s images do not always need to be so sketchy to give the viewer such an intensive impression. In Constant’s work, even a map can become the playground on which an ambient vision of urban space is provoked. In “New Babylon North” (Figure 5), Constant maps out an imaginary city plan, which, from a distance, might as well be perceived as a haphazardly marked blotchy piece of paper. Leaving aside conventional techniques to make maps, Constant here composes an almost child-like collage, in a way quite different from the appropriated maps. This time, he does not have an actual map in the background; instead, the background is almost empty. What fills in this empty space is a set of winding lines that are spread all over the surface, constituting nodes at the points where they intersect. The mis-en-scène is completed with white strips of paper irregularly pasted onto the background and watercolored in black and red.

“New Babylon North” suggests a nomadic quality[xxvi], with “flexibility” and “play” figuring as vital elements of space[xxvii]. Even in this highly restrictive medium of spatial representation, Constant performs a ludic behavior to distort its conventions thus turns the map into another kind of labyrinthine structure. At this very point, Constant’s nomadic map becomes less an attempt to represent space than a resistance to and an attack on representations of space. Therefore, the polemical value of the “New Babylon North” displaces its practical value, rendering the supposed opposition between “everyday life” and “utopia” obsolete.

Concluding Remarks—Antinomy Perfected

Constant’s New Babylon is neither a “utopian” project nor a “realistic” proposal for a future city. Rather, it is a form of propaganda, or an indeterminate form of critique (Wigley, 1998). Instead of constituting an end in itself, it defies the blind alleys determined by the ones bound by those ends; and it opens the way to new questions that entail new openings. By sustaining indeterminacy, Constant resists the hegemonic attempts to stabilize spatial relations and close down space. In this sense, the New Babylon is a form of resistance to the existing spatial conditions. It is a non-deterministic but still a revolutionary way of conceiving the outlines of a future spatiality. Its contradictions are never resolved (not even meant to be so); instead, they are deliberately pushed to their extremes, making its antinomic quality perfected to the full.

In Constant’s work, there is an attempt to bridge the discontinuity not only between practice and theory, but also between the process of creative production and its representation—just as in Situationism, which conceives immediate action and total revolution as interconnected. Definitely for this reason, in Constant’s New Babylon, as well as in Situationist politics of space, the two seemingly contradictory aspects of the desire for total change and the impatience to intervene into everyday life are far from incompatible. Rather, they do produce a constructive conflict. However, neither Constant’s work nor Situationist politics aims at a reconciliation. Instead, they both face this conflict, take it to its extremes, sustain it, and look insistently into the antinomy created by it, making the intermediate zone between the two polar opposites the locus of their operations. Situationist space draws attention to the grey area between utopian and anti-utopian conceptions of social change. Furthermore, it makes us reconsider the “idealism” widely and quite easily attributed to utopian thinking, which makes it seem like a dead end in itself.

The New Babylon is a space of sustained conflict; it is “an uncanny world” (Wigley, 1998: 69). This creates a constant resonance and gives Situationist space a tragic and cyclical quality, which is very well reflected by the Latin palindrome used by Debord as the title of one his films: “We go round and round in the night and are consumed by fire”. Andreotti interprets this cyclical quality as one that could reach such a point where it would not mind ruining itself (Andreotti, 2002: 236-237). In a later commentary on the Situationist International legacy, Debord himself also remarks on this cyclical form: “All revolutions go down in history, yet history does not fill up; the rivers of revolution return from whence they came, only to flow again” (Debord, 1991: 25).

Situationism undertook the hard task of preferring not to resolve but to sustain the conflict hence constantly “keeping abreast of reality” (Marcus, 2002: 16). Seen in this way, one might say that Situationists might well have been the victims of their own agonism, feverishness and perversity—those qualities that are mostly considered politically inappropriate. Nevertheless, I do think that the inclusion of these qualities in politics is a strength rather than a weakness. As Chantal Mouffe puts it:

Political actors are conceptualized as rational individuals driven by rational interests. Passions are erased from the realm of politics, which is reduced to a neutral field. This approach forecloses the possibility of grasping the dynamics of antagonism. Indeed, the aim of politics is to transform an antagonism into an agonism. (Mouffe, 1999: 154).

Constant noted in 1965 that the New Babylon would never be concretely realized nor be finished. It will rather be a ceaseless activity in which “all the people that are to live will be involved” (Wigley, 1998: 67). Constant’s creative production and the Situationist conceptualization of space remained unrealized in the common sense of the term; but both have definitely been realized in their influences on later critical thought on space. This legacy deserves interest not only for turning the antagonistic political dynamic of the 1960s into an agonism, but also for its distinctive way of articulating an indeterminate politics of space, which, today, needs to be faced by the ones thinking over the possibility of revolutionary space.

These remarks may as well reveal a sense in which Situationist way of thinking becomes closest in form to poetry. Claiming that “tomorrow life will reside in poetry”, Situationists made the poetic indeterminacy the only moment of reality. Both everyday life and utopia were tragic, yet they both offered possibilities. This lived tragedy is best expressed in a pre-Situationist text of 1953—later published in the first issue of Internationale Situationniste:

And you, forgotten, your memories ravaged by all the consternations of two hemispheres, stranded in the Red Cellars of Pali-Kao, without music and without geography, no longer setting out for the hacienda where the roots think of the child and where the wine is finished off with fables from an old almanac. That’s all over. You will never see the hacienda. It does not exist. The hacienda must be built. (Ivain, 1953: 1).

Endnotes

[i] In this paper, I draw on some of the studies that fall into this category. See McDonough, 1994, 1997 & 2002; Sadler, 1999; Wigley, 1998; and Wollen, 1989 & 2001.

[ii] This is the title of an article published originally in French in the third issue of the Situationist International journal (Internationale Situationniste, no.3, December 1959). The English translation is included in Wigley, 1998, pp. 115-116.

[iii] Constant was a member of CoBrA (1948-51) and later the Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus (1954-57), which, came together with the Lettrist International (1952-57) at the First World Congress of Free Artists in September 1956, through which the Situationist International was founded. CoBrA (abbreviation originating from the initials of Copenhagen, Brussels, Amsterdam) was a group of avant-garde artists who undertook the revolutionary task—both practically and theoretically—to transform the bourgeois conception of art by drawing on the legacy of the pre-World War II surrealism and a heterodox / libertarian Marxism. The Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus was founded by Asger Jorn, bringing together some of the old CoBrA artists and a new Italian faction around Pinot Gallizio, whose collaboration would later be decisive in the First World Congress of Free Artists that took place in his hometown, Alba-Italy; thus the founding of the Situationist International (Sadler, 1999).

[iv] The Economic Recovery Program (ERP)—widely known as the Marshall Plan—was a planned economic assistance provided by the US to European countries. The overall objective was to help overcome the economic and political crisis Europe faced in the aftermath of World War II, hence stabilizing the international order in a way favoring the development of free-market economies. Having its origins in the Truman doctrine of 1947, the program started in 1948 in 18 countries, and ended in 1951. For more detailed information on the Marshall Plan, see the online exhibit “For European Recovery: The Fiftieth Anniversary of the Marshall Plan” (held at the Library of Congress between June 2nd and August 31st, 1997) on the Library of Congress website: http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/marshall/

[v] The subject of Debord’s criticism was first and foremost the capitalist world-system. However, he also took issue with the totalitarian tendencies of “the old left”, as manifest in Soviet socialism. In this paper, I mainly focus on his criticism of capitalism. Nonetheless, some of the criticisms I include here also apply to Soviet socialism, as in the case of bureaucratic state power.

[vi] Furthermore, in his later book Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, Debord argues that the concentrated and the diffuse forms of the spectacle have since then been incorporated into a third form, the integrated spectacle, on the basis of a general victory of the diffuse (Debord, 1998: 8-11). In fact, one could trace the manifestations of this incisive analysis by Debord, just by looking closely at what happened within the two decades following the publication of The Society of the Spectacle (1960-80).

[vii] Widespread access to the private automobile was made possible with the rapid growth of the automobile industry, bringing with it the widespread improvement of highway networks.

[viii] The suburbia was the dreamtown of this new urban landscape. For an extensive study of the social history of housing in the United States, see Wright, 1981. For an analysis of suburbia in relation to the politics of consumption in postwar America, see Cohen, 2003. For an analysis of popular media in relation to postwar suburbs, see Spiegel, 2001. Later on, postwar urbanism was criticized for causing the loss of the sense of place. For an early criticism of this kind, see Jacobs, 1961. For a later criticism, see Duany et al., 2001.

[ix] Spiegel discusses not only how television physically became an element of the standardized suburban homes, but also how it helped spread the ideology of the American dream. As an example, Spiegel mentions the myth of outer space—as part of the discourses of the Cold War era—entering the domestic space by way of phantasmic family sitcoms (Spiegel, 2001).

[x] In Fast Cars, Clean Bodies, Ross talks about the decade between 1958 and 1968, which more or less corresponds to the time when the Situationists were active (1957-1972). Also, both Ross and the Situationists consider this time as the period when the postwar social transformations in France reached its peak point. Therefore, I find it safe to see Ross’s account of French cultural history as a backdrop to Situationism (Ross, 1995).

[xi] Ross also discusses the dominance of language thus the significance of communication as a key ideological concept in French culture. For Ross, this suggests to think of a relationship between French structuralism and the technologies entering the domestic interior. As a humorous example of this, Ross notes an instance in Jacques Tati’s 1958 film Mon Oncle (My Uncle). At this moment in the film, one of the protagonists, Madam Arpel, gives utterance to her fascination with the domestic technologies in her own suburban house. She shouts in excitement: “Everything communicates!” (Ross, 1995: 6, 191).

[xii] According to Peter Wollen, who traces the connections between Situationism and critical Marxist thought, the idea of “constructing situations” was hinged upon two main sources; the works of Sartre and Lefebvre. Wollen claims that Situationism takes the concept of situation from Sartre’s existential Marxism, combines it with Lefebvre’s critique of everyday life and arrives at a synthesis of the two, in which Sartre’s situations are not accepted as given, but become both the subjects and the means of realizing the Lefebvrian transformation of everyday life. See Lefebvre, 1991b; Wollen, 1989. I would add to Wollen’s account that “constructing situations” also owes to the theory of moments, developed also by Lefebvre. For Situationism’s articulation of Lefebvre’s theory of moments, see Internationale Situationniste, 1960.

[xiii] This involves a criticisim of the Chicago School of urbanism. Developed by Robert Park and Ernest Burgess at the University of Chicago between 1915-1940, the Chicago School of urbanism conceived the city as an ecological system, and assumed that cities evolved through selection, adaptation and organic growth, just as in the Darwinian model of human ecology. According to Constant, this approach overemphasizes how the inhabitants shape the city while disregarding how the city shapes them. Psychogeography, on the other hand, proposes to think of this process as an interaction functioning both ways at one and the same time (Nieuwenhuys, 1960).

[xiv] The term “unitary urbanism” was first mentioned in a text by the Lettrist International presented to the First World Congress of Free Artists in September 1956. Afterwards, Constant elaborated it further in conjunction with his project New Babylon. See Ivain, 1953; Nieuwenhuys, 1960.

[xv] In the concept dérive, one can trace the legacy of Surrealism. See Wollen (1989) who gives a detailed account of Surrealist influences on Situationism. In fact, Debord treats surrealist experiments with drifting as inferior to dérive; mainly for two reasons. First, being bound by chance encounters, they were more passive than active. Second, taking place in the countryside rather than in the very heart of the city, they represented an escape from the urban environment, which, for Debord, had to be faced in the first place (Debord, 1958: 52-53).

[xvi] I work out the concept of “the misuse value of space” more extensively in an unpublished paper titled: “The Misuse Value of Space: Oda Project’s Spatial Operations”.

[xvii] Although Situationists had an uneasy relationship with Lefebvre, they were definitely influenced by his work.

[xviii] Here “reification” stands out as a significant Marxist concept giving shape to both Lefebvre’s critique of everyday life and Debord’s theory of the society of the spectacle (Lefebvre, 1991b; Debord, 1995). Wollen elaborates on Debord’s theory in relation to Marxist understanding of commodification; and he sees a Lukács connection via the concept of “reification” (a modified version of Marx’s commodity fetishism) (Wollen, 1989).

[xix] A concrete example of this attempt is the full-size labyrinth that Constant built for the exhibition at Gemeentemuseum in the Hague in 1965. See Wigley, 1998: 51.

[xx] At the time, Constant was also producing both experimental and more conventional works in singular mediums such as sculpture. For Constant’s experiments with sculpture and his realized public sculpture projects, see Wigley, 1998, 22-25.

[xxi] The sectors are the smallest units of construction that make up the New Babylon. For a more detailed definition, see Nieuwenhuys, 1974.

[xxii] The models were dated 1969, while the photomontage was made in 1971. See Wigley, 1998: 194-196.

[xxiii] In terms of scale, these maps liken more to large scale city plans than to detailed urban design projects. The scales of the maps are mostly not specified; and they are not all the same. Only the scale of the Munich map is visible, which is 1:20.000; and this is the scale of city planning in which decisions only about general urban functions (commercial districts, residential areas, etc.) are made. Making decisions on more minute details of urban life requires the use of smaller scales (such as 1:5000, 1:1000). In fact, with respect to urbanism proper, all these different scales are quite strictly divided between the sub-disciplines of planning. The smaller scales and the decisions concerning them fall into the field of urban design; they are not supposed to concern city planners.

[xxiv] Constant was always eager to use the medium of film. His 1959 Stedelijk Museum exhibition in Amsterdam featured films of early New Babylonian constructions. In 1968, another film about the New Babylon was made for German television. Indeed, in a lecture in 1964, Constant insisted that his images are “tentative” in the sense of being just “space-time moments” in the continual remaking of the New Babylon: They were “fixed points in a spatial system whose only feature is restless movement”. Yet another instance was a lecture in 1964, where Constant asked the audience to consider his slides as “stills from a movie” he intended to make (Wigley, 1998: 55, 58). In fact, cinema had always been an important medium for the Situationists. Debord made films that were not only political commentaries but also experiments with the medium itself. For a discussion of Debord’s films, see Agamben, 2002.

[xxv] This claim derives from Gilles Deleuze’s work on cinema. For him, cinema is not a language—as structuralists would have it—but a medium that exceeds the workings of language. For Deleuze’s conception of cinema as space-time image, see his extensive and very influential study: Deleuze, 1986.

[xxvi] In fact, in 1957, Constant designed a nomadic settlement, inspired by a gypsy community he was acquainted with during his stay in Italy earlier. This was an imaginary gypsy camp made up of changeable and transportable structural elements. See Wigley, 1998; and Andreotti, 2002.

[xxvii] For an elaboration on the Situationist conception of play (derived from the notion of “homo ludens” articulated by Dutch historian Huizinga), see Andreotti, 2002.

Works Cited

Agamben, Giorgio (2002) “Difference and Repetition: On Guy Debord’s films”, in Thomas McDonough (2002) (Ed.) Guy Debord and the Situationist International, Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 313-320.

Andreotti, Libero (2002) “Architecture and Play” in Thomas McDonough (2002) (Ed.) Guy Debord and the Situationist International, Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 213-240.

Arrighi, Giovanni; Hopkins, T. K. & Wallerstein, I. (1989) Antisystemic movements, London & New York: Verso.

Cohen, Lizabeth (2003), A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Random House.

de Certeau, Michel (1984) The Practice of Everyday Life (Trans. Steven Rendall), Berkeley: University of California Press.

Debord, Guy and Gil J. Wolman (1956) “A User’s Guide to Détournement”, in Ken Knabb (1989) (Ed. & Trans.) Situationist International Anthology, Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, pp. 8-13.

Debord, Guy (1958) “Theory of the Dérive”, in Ken Knabb (1989) (Ed. & Trans.) Situationist International Anthology, Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, pp. 50-54.

-- (1961) “Perspectives for Conscious Alterations in Everyday Life”, in Ken Knabb (1989) (Ed. & Trans.) Situationist International Anthology, Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, pp. 68-75.

-- (1991) Panegyric, New York: Verso.

-- (1995) The Society of the Spectacle, New York: Zone Books.

-- (1998) Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, New York: Verso.

Deleuze, Gilles (1986) Cinema 1: Movement-Image, University of Minnesota Press.

Duany, A., Plater-Zyberk, E. & J. Speck (2001), Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream, North Point Press.

Ivain, Gilles [Ivan Chtcheglov] (1953) “Formulary for a New Urbanism” (Translated by Ken Knabb), Internationale Situationniste #1 [Situationist International Online: http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/presitu/formulary.html].

Jacobs, Jane (1961) The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

Lefebvre, Henri (1991a) The Production of Space (Trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith) Blackwell Publishing.

-- (1991b) The Critique of Everyday Life I (Trans. John Moore) New York: Verso.

Marcus, Greil (2002) “The Long Walk of the Situationist International” in Thomas McDonough (2002) (Ed.) Guy Debord and the Situationist International, Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 1-20.

McDonough, Thomas (1994) “Situationist Space”, October 67, Winter 1994, pp. 59-77.

-- (1997) “Rereading Debord, Rereading the Situationists”, October 79, Winter 1997, pp. 3-14.

-- (2002) “Ideology and the Situationist Utopia”, in Thomas McDonough (2002) (Ed.) Guy Debord and the Situationist International, Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. ix-xx.

Mouffe, Chantal (1999) “Globalization and Democratic Citizenship”, Working Papers in Local Governance and Democracy 99/2, Istanbul: WALD, pp. 152-158.

Nieuwenhuys, Constant (1960) “Unitary Urbanism”, in Mark Wigley (1998) (Ed.) Constant’s New Babylon: The Hyper-Architecture of Desire, Rotterdam: Witte de With Publishers, pp. 131-135.

-- (1974) “New Babylon: Outline of a Culture”, in Mark Wigley (1998) (Ed.) Constant’s New Babylon: The Hyper-Architecture of Desire, Rotterdam: Witte de With Publishers, pp. 160-165.

Ross, Kristin (1995) Fast Cars, Clean Bodies: Decolonization and the Reordering of French Culture, MIT Press.

Sadler, Simon (1999) The Situationist City, Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Spiegel, Lynn (2001) Welcome to the Dreamhouse: Popular Media and Postwar Suburbs, Duke University Press.

Wigley, Mark (1998) “The Hyper-Architecture of Desire” in Mark Wigley (1998) (Ed.), Constant’s New Babylon: The Hyper-Architecture of Desire, Rotterdam: Witte de With Publishers, pp. 9-71.

Wollen, Peter (1989) “The Situationist International”, New Left Review 174 (March-April 1989), pp. 67-95.

-- (2001) “Situationists and Architecture”, New Left Review 8 (March-April 2001), pp. 123-139.

Wright, Gwendolyn (1981), Building the American Dream: A Social History of Housing in America, New York: Pantheon Books.

Situationist International (1960), “The Theory of Moments and the Construction of Situations” (Trans. Paul Hammond), Internationale Situationniste #4 [Situationist International Online: http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/moments.html].

“For European Recovery: The Fiftieth Anniversary of the Marshall Plan” (Exhibition held at the Library of Congress between June 2nd and August 31st, 1997). [Online exhibit, the Library of Congress website: http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/marshall/]

Deria Ozkan, [Univ. Rochester, USA] studied architecture at the Middle East Technical University in Turkey. Getting more interested in the critical analysis rather than the practice of architecture led her to publishing, and she worked as an editor for five years. Following a year of research assistantship at Istambul Bilgi University, she pursued graduated studies at Maastricht University and got her MA degree in 2001. Currently, she is a Ph.D. student at the University of Rochester.

|